An essay written for the course Metropolitan Innovators of the joint master (TU Delft, Wageningen UR & AMS Institute) Metropolitan Analysis, Design & Engineering

DELICIOUS MEALS FROM FOOD WASTE

ANALYSIS OF THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL PROBLEM OF FOOD WASTE, THE RISING SOLUTIONS AND OPPOSITIONS CONCLUDING IN A QUEST FOR SOLIDARITY

INTRODUCTION

88 million tonnes of food are wasted in Europe per year, of which the Netherlands with 2,3 % of the European inhabitants has a large share of 10,8 % with 9,5 million tonnes food wasted per year (Bio Intelligence Service, 2010, p. 56). Worldwide we waste nearly one third of the food produced for human consumption (Tonini, 2018). On average, we waste 113 kg of food per person per year in the Netherlands. The only countries that waste more food per capita, are the UK and Luxembourg. Luckily, food waste prevention is becoming more and more important in political agendas, as is it in people’s moral decisions.

Koester (2014) defines food waste as food appropriate for human consumption that is discarded regardless of expiry date, intentionally discarded by the end user for various reasons that are categorised in avoidable and unavoidable. Avoidable food waste is defined as food that was edible at some point along the supply chain, and mostly discarded for not meeting market standards for visual appeal. Due to the modern ubiquity and accessibility of information, coupled with mass globalization, societies have ingrained certain standards into cultural norms, which in turn has driven consumers to develop high expectations on availability and perfection of their consumables and partial acceptance towards deviation (Gustavsson et al., 2011). The odd shaped pear or curly cucumber probably end up in a bin. Unavoidable food waste refers to food waste that is inedible for human consumption such as banana peels, bones, and other inedible substances (Salhofer et al., 2008).

This article will discuss the topic of food waste from a multidimensional view. I will start with a broader perspective on the problem, by sketching the historical path that food waste creation has taken from being a technical issue to being an almost fully socially engrained issue nowadays, using the socio-technical approach. Relevant sustainability goals regarding food waste are discussed as well as the circular economy strategy. The ecosystem approach is used to gain in depth insights into the production of food waste in the food supply chain, with a focus on the supermarket and their main motives for either incinerating the food waste or donating is for its main purpose: human consumption. A sample is taken from the currently practised ways of preventing food waste, on a general note as well as specifically in Amsterdam. The solutions in the city are viewed in a spatial justice perspective, locating them within the current governance and a closer look to the addition they make to the equality of resource division in the city. The article is closed off with some rising initiatives to make food rescuing more playful and accessible.

A SOCIO-TECHNICAL CHALLENGE

Our current Western society is leaning on modern technology, for nearly all processes of daily life, including work, communication and food consumption. Because society depends on technology, and technology facilitates society we can look at this double play as one complex socio-technical system (Geels, 2005). Geels (2005, p. 446) describes his definition of a socio-technical system consisting of “a cluster of elements, including technology, regulation, user practices and markets, cultural meaning, infrastructure, maintenance networks and supply networks”. Regarding food, technology plays a role in transport from the farms and factories that produce the food to the cities where we live as well as modern packaging and cooling to preserve it until the specific product ends up in our luxurious meal, to start with. To a large extent this technology creates the efficient supply chain there is and saves a lot of food from being wasted.

Past causes for food waste were bad weather conditions, and missing infrastructure, technology or hygienic conditions. In general, the former generations had completely different notions of hygiene and ethics, which can be demonstrated with the 14th century order by Peter IV of Aragon. He let the stale and mouldy bread, acetified wine, spoiled cheese and fruit be donated to people in need, with the also shared by doctors in that time hypothesis that the lower classes could eat spoiled food without any harm (Montanari, 1999). The first food regulations were set into force during the 15th century, amongst which a law to ensure the mass and quality of certain loaves to everyone, as bread was a staple food product. Underweight loaves were confiscated by the authority and given to the city hospital for example (Schubert, 2006). Where in the past food waste could often not be controlled by human beings (Schneider, 2013), the food waste problem is transitioning into one that is caused by humans’ high expectations, thus socially rather than by a lack of technology.

Still in the current time, social and technological aspects are present. A first distinction between the technical and the social part of the problem can be made by depicting food waste next to food loss. As opposed to food waste that is purposely discarded by consumers, food loss is defined as the food that was originally intended for human consumption but was lost somewhere along the food supply chain. Food losses include the crops and livestock that completely exit the post-harvest, slaughter production, or supply chain by being discarded, incinerated, or otherwise disposed of (FAO, 2020). An example is the lack of necessary technologies and infrastructure to maintain freshness of food and transport the food efficiently in less industrialized nations (Hodges et al., 2011). Coinciding with the environmental aggravation of extensive land use and degradation of the soil, human health is also impacted among regions of people who live near the land. The amount of food that is lost or wasted along the entire supply chain is sufficient to feed the world’s hungry four times over (FAO, 2020).

SUSTAINABILITY GOALS

The United Nations (2018) included the topic of food into different Sustainable Development Goals. Such as in goal 2, describing hunger reduction and goal 12 describing responsible production and consumption. The European Commission (EC) has set the goal to reduce half of the food waste by 2025 (EP, 2012). The FAO (2011) mentions that in wealthy countries such as the Netherlands relatively low prices in combination with the oversupply of food results in relatively high levels of food waste compared with lower income countries. As Stenmarck et al. (2016) state, households contribute 53% of total food waste generation at EU level, followed by food processing, food service, food production and wholesale and retail (respectively, 19%, 12%, 11%, 5%). Stenmarck et al. (2016) make an estimation of 88 million tonnes of food waste generated throughout the whole food chain by the EU-28 country members every year.

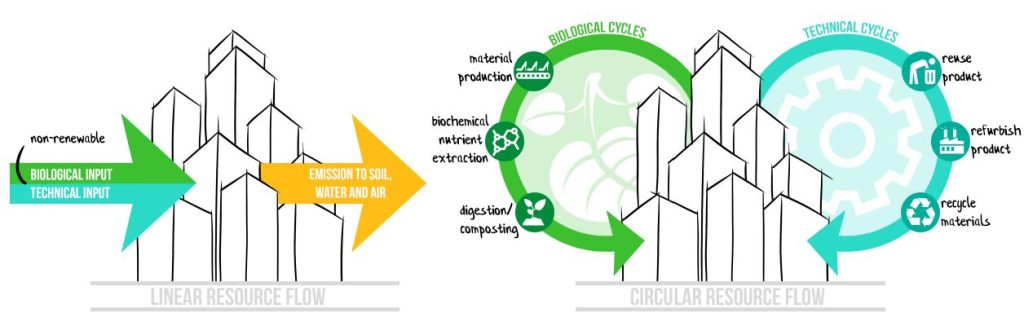

The Netherlands strives to halve the use of primary raw materials by 2030 and have a fully circular economy by 2050 (Rijksoverheid, 2019). A circular economy means that no waste is produced, and no primary raw materials are used. Therefore, the products that we would want to use in our daily lives have to be manufactured using materials recycled or reclaimed from waste streams. Figure 1 shows the current linear resource flow next to the ideal circular resource flow.

Transition from a linear use of resources and waste production to circular flows with sustainable management of resources, will allow cities to increase sustainability in social, economic and ecological ways for future generations. The circular resource flow is characterized by two distinct routes in the Urban Harvesting Concept (UHC): one for biological and one for technical materials, which have new end-of-life uses instead of becoming waste (van der Hoek et al., 2017).

Geissdoerfer e.a. (2017) define a circular economy as “a regenerative system in which resource input and waste, emission, and energy leakage are minimized by slowing, closing, and narrowing energy and material loops”. The most important message is the reframing of waste from an unwanted by-product of linear economic activities, to a valuable resource. In the circular economy the final disposal options for the biological cycle, the focus of this essay, are categorised from most to least desirable; reduce, reuse, recycle, compost, incinerate and landfill (MacArthur, 2013).

SUPERMARKET ECOSYSTEM

The supermarket ecosystem defines an environment in which food is sold and bought and where company policy heavily influences the production of what can become large quantities of avoidable food waste. To consider the ecosystem of an organisation, an overview is made of the larger system it is embedded in, the flows of materials that are involved and to what extent these flows are organized in a circular fashion. The proposed and applied solutions have to be valued in terms of their social, economic and environmental sustainability. Tuominen (2010) states that as opposed to reductionism that breaks reality down into components to study separately, the systems theory aims to reveal all interdependencies and connections for a holistic interpretation of societal challenges.

At the online supermarket Crisp, part of the Food Center of Amsterdam, the main importer and exporter of food in Amsterdam, located in the west of the city, customers order their food via the website and get it delivered in electrical vehicles. The supermarket aims at high-end, local and fresh products, which results in large quantities of food disposal when the product cannot be guaranteed to stay fresh for at least a week. Eggs must even have an expiry date of at least 3 from date of sale. This high standard and customer service results in large quantities of unsold goods that have an expiry date of 1 to 5 days in the future, and for the eggs even up to three weeks, placed in the ‘derving’ (rotten) recks where employees are allowed to pick 2 pieces to take home after their shift. On a weekly basis, it is estimated that around 2,000 kilograms or more of fresh products are placed on the ‘derving’ cart. While employees take a minimal portion, the food banks and the food rescue organizations take a majority of this and distribute it to the community. Each food rescue organization has a designated day that they collect the food from the ‘derving’ cart. The amount of food on the ‘derving’ cart frequently exceeds the amount of food that the food rescue organizations have capacity for. Among the food distributors that the food rescue organizations collect food from, the majority of their food comes from this online supermarket. It is often here where crates of milk and cheese are found. Mountains of ready-made meals and soups are an abundant source. The remaining food that is not collected by the end of the week is discarded into the municipal solid waste stream since organic waste does not get separated in Amsterdam, is transported to the incineration plant to be burned for energy recovery.

As Amsterdam aims to become a city with a circular economy, many businesses have begun to conform to the new regulations and so did the Food Center. Organic waste treatment plays a large role in the strategy of the City of Amsterdam, with rising interest in options like composting and anaerobic digestion. While these are solutions to treat unavoidable food waste, they are not appropriate for avoidable food waste. In the aim of becoming more sustainable, the Food Center of Amsterdam is planning to distribute their food waste to an organic treatment facility in order to be converted into biofuels. However, the current situation withstands that the distributors within the Food Center have an unwritten agreement with local food rescue organizations (Robin Food among others) that collect the food waste and distribute it to the community. The new developments of establishing an agreement with the organic waste treatment facility will eradicate the existing relationship between Crisp and the food rescue organizations. As a result, thousands of kilograms of edible, avoidable food will be discarded and hundreds of people will be impacted due to the lost food. Furthermore, the new development of the Food Center is not in alignment with the strategy of the Circular Economy as the first step along the waste hierarchy is prevention.

DATE LABELLING

According to the report made by the European Commission (2018) there is approximately 8,8 million tonnes of edible food wasted due to date labelling across the manufacturing, retail and household sectors in the EU. This is 10% of the total amount of avoidable food waste and equates to 3 to 6 billion euros per year (Lee et al., 2015). The food categories that are mainly contributing to this amount of waste are vegetables & fruits, dairy products, bread and meat (including poultry and fish). The main cause here, is that consumers do not know the difference between the Use By date, that is created for safety reasons on highly perishable products, and the Best Before date that only implies the guarantee of the initial quality of the product by producer/seller, but the product can still be used after this date. Supermarkets are allowed to sell products with an expired Best Before date. On the other hand, the European Commission (2018) found that many consumers have become date-mark dependent in the scale that they no longer trust their own senses to understand if the product is suitable for consumption or not. Figure 2 shows the by New Zealand collective LoveFoodHateWaste (2020) created flyers that are part of their education program on expiry dates since they figured that knowing the difference between ‘use by’ and ‘best before’ is important in reducing food waste. The European Commission (2019) states in the newest report on food waste prevention, that a change in requirements to food labelling within the EU is needed. New labelling guidelines should enhance well-informed consumers, contribute to the reduction of food waste and guarantee food safety to consumers.

THE RIGHT TO RESCUE FOOD IN THE CITY

Paradoxically, the percentage of food being wasted increases at the same time as the percentage of food insecure people around the globe. In the period from 2003 to 2011 food insecurity in the Netherlands rose from 0.3% to 2.0% of the total population (Davis & Geiger, 2017). The logical suggestion would be that municipal policy-makers encourage the redistribution of potentially useful goods between local businesses and willing recuperators. However, food waste retrieval from the bin is forbidden by local laws in most regions in the Netherlands. The municipality Haarlemmermeer, adjacent to Amsterdam in the south-west, has for example written in their administrative law (Dutch: bestuursrecht) that “it is prohibited to hand over household waste or to offer it for collection to anyone other than the collection service” (translated from Dutch; Gemeenteraad Haarlemmermeer, 2006, article 11.2).

While in the past retrieving perfectly edible food from the bins was very accessible throughout the country, and especially common in the bigger cities in the Netherlands, the bins are nowadays placed inside the fences everywhere and the largest supermarket chains have included in their regulations that the procurement of food waste from the bin or taking it home by employees is strictly forbidden. Opponents to dumpster diving say that the large mess that the divers often leave is their largest concern, especially heard from shop owners and managers. Other arguments read in online discussions regard the safety of the divers and the legal aspects. Easy measures such as thick gloves and poking sticks are taken and the responsibility here is clearly on the side of the people searching for food.

Those arguments are mostly given to hide the actual anxiety: losing profit because food is obtained for free. The dumpster divers themselves often see it as a political act of radically boycotting a capitalist economic system that is solely based on the pursuit of profit, which makes the skippers unwanted by the profit seeking supermarkets that like a consumerist mindset in their customers. Into account has to be taken that disliking illegalities and thus dumpster diving is common for most citizens and shop owners.

According to Harvey (2008) “The right to the city, as it is now constituted, is too narrowly confined, restricted in most cases to a small political and economic elite who are in a position to shape cities more and more after their own desires.” He elaborates upon the question of who guides the needed connections between urbanisation and surplus production and use. The geographer Soja (2009) gives “the fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and the opportunities to use them” as a starting point for creating a socially just city. Rocco (2017) adds a distinction between distributive justice, the share of resources as described by Soja, and procedural justice referring to the equal share of inhabitants in the processes of planning, design, laws and regulations themselves. In order to get equality and procedural spatial justice, non-expert views that are often not heard in decision processes, for which the understanding of these governance structures is very important (Rocco, n.d.).

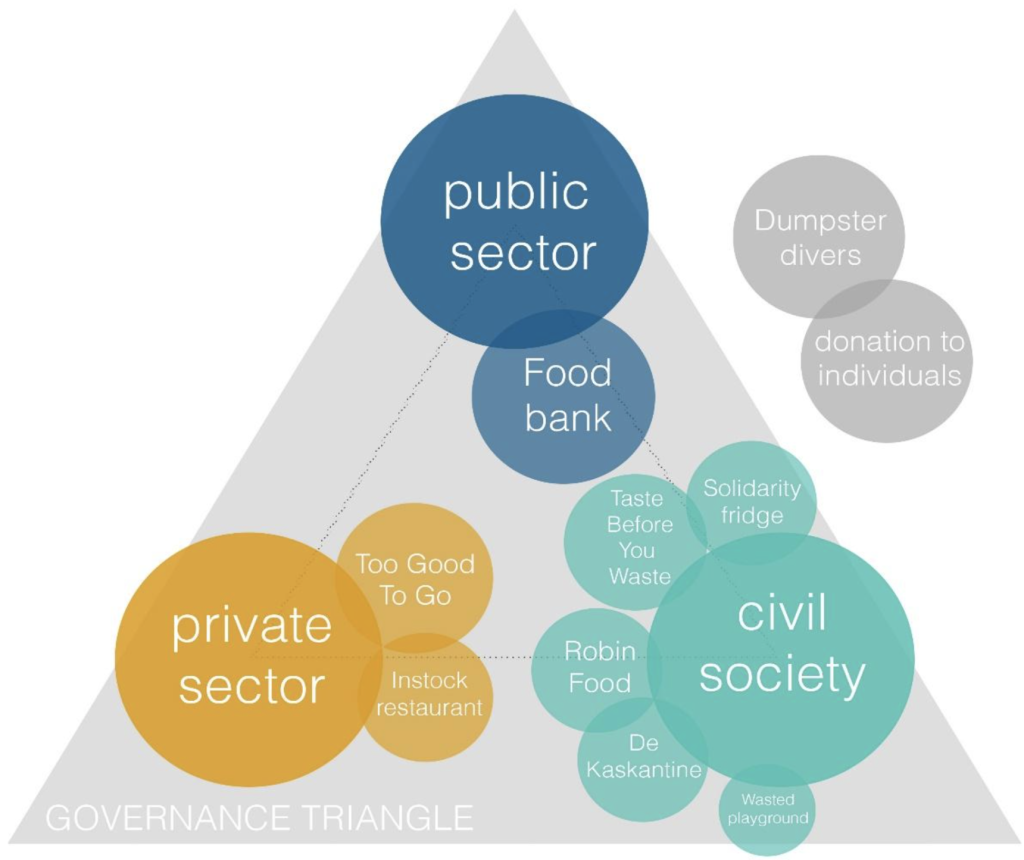

Loorbach (2010) defines governance as the practice to develop policies in interaction with a diversity of societal actors. Those societal actors are depicted in the governance triangle (figure 3) as the public sector, government bodies such as municipalities, national or supranational agencies, the private sector are the companies and corporations and civil society are citizens that unite for a cause such as NGO’s, social or religious movements. Together with informal norms based on culture and tradition, these actors determine the governance in practice by their way of interacting(Rocco, n.d.). To consider the extent of spatial justice within the challenge area, the involved stakeholders that are actively coming with solutions are depicted in the governance triangle. Another important topic to consider to define the extent to which those initiatives add to a justly divided right to the city, is the openness of their created goods to the public. To what extent are those solutions to wasting food accessible to the entire population, and especially the ones that need it most?

FOOD RESCUE INITIATIVES IN AMSTERDAM

Many solutions are grass rooting from the bottom in society up, so not coming from the state but from (rebellious) individuals or collectives. With a focus on the local actions in the region of Amsterdam, two tactics to reduce food waste through prevention can be distinguished. Firstly, food waste can be secretly taken from the bin at the back-end of the grocery store, also called dumpster diving (US) or skipping (UK). The second approach for saving food waste is by kindly asking the shops what they have left over for donation and in this way creating easiness for the shops as well since they have less food to throw away at the end of the day. This second approach is one that I practise on a weekly basis at minimum. The Turkish vegetable shop in my street is happy to give his left-overs away, and in exchange I do the rest of my groceries in his shop and sometimes invite him for dinner or share the banana bread, made from his left-over bananas with his family. This is an example of donation to individuals. The food rescue collectives that are discussed in this section exist through donations of shops as well, mostly based on strict agreements on a regular pick-up moment.

The research done by Vinegar et al. (2014) retrieved data by participant observation and semi-structured interviews in Montréal, Canada and found that while some dumpster divers identified as food insecure and extremely poor, most did not. Most food insecure people save food from being wasted from need, to supplement food from, or to avoid the stigma that goes with social assistance, like the Food bank in the Netherlands that gives out mostly simple food for free to the poorest population. The European Federation of Food Banks was established in 1984 and more than 30 years later there are 247 food banks that support approximately 5.2 million people in Europe (European Food Banks, 2007; Schneider, 2013). On the other side, food-secure divers in Montréal, mostly university students, have strong social connections because they frequently exchange knowledge and goods and hold common values. Found in the interviews is that specialised knowledge is needed for the diving and that mostly recuperated is food waste from grocery stores and bakeries (e.g. breads, fruits, vegetables, meat, dairy products) that significantly improved the composition and quality of diets the participants could otherwise afford (Vinegar et al., 2014).

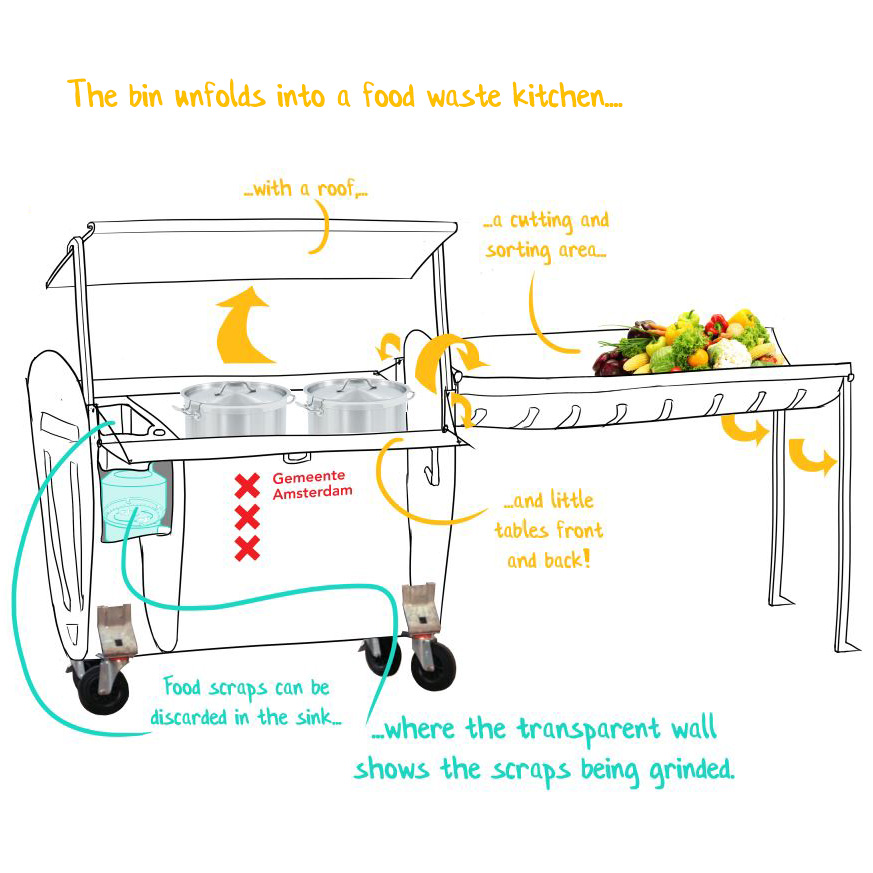

The donation of still edible food can be seen as the most wanted application of urban mining as food is recovered from a mismanaged society for its original purpose – human intake. There are several projects implemented worldwide but due to a lack of data, scientific literature about the topic is rare (schneider, 2013). The following section of this essay summarises briefly the evolution of food donation collectives, and even some businesses in Amsterdam, gives information on the differences and similarities of current organisations distributing food to people in need as well as the political, legal, social and logistical barriers and incentives which occur with respect to this topic. A concept for a food donation network that is currently set-up by some fanatic food savers is presented as well as the wasteless bin that turns into a kitchen for food waste prevention and awareness creation intentions that I designed myself. Impact on ecology, economy and society is discussed.

WASTELESS DINNERS

Besides those non-profit organisations that fight against the food waste, some people did find a way to make a living from the rescue of food by creating a successful business. The restaurant Instock produces high-end meals for normal restaurant prices in a normal restaurant setting. The special element about the restaurant is that all their ingredients were supposed to be wasted by Ahold Delhaize, the international retailing conglomerate that the largest supermarket chain in the Netherlands Albert Heijn is also part of. In this way the odd shaped pear or curly cucumber exchange the bin for a delicious salad, as can be done though the mobile application Too-Good-To-Go that has the core aim of making the consumption of rescued food as easy as possible for consumers. The app saved over a million bags with food since its establishment in 2018 from the over 2000 participating locations in the Netherlands (TooGoodToGo, 2020). Consumers can legally purchase a “Magic box” from a participating shop, for prices that are about one third of the value of the content. The Too Good To Go platform places a large focus on the communication and awareness creation aspect of the food waste problem. On the website there is all you need to ever know about food waste available, well-written and substantiated with proper research and resource records. The Too Good To Go app seems to be focussing more on the higher income classes, since they do still ask substantial money for their “Magic boxes” and they can only be obtained via the smartphone application and paid by credit card, an object that many low-income people in the Netherlands do not standardly own.

Figure 4 a-c: Robin Foods food rescue and community activities, from left to right (a) from Food Center rescued food for food delivery bags, (b) community building evening and (c) bike delivery of food bags (own images)

The in figure 3 as belonging to the civil society (light blue) depicted food rescue organizations are all completely volunteer driven and do not make profit. Robin Food collects food from the Food Center of Amsterdam on a weekly basis (figure 4a). Every Monday, the cooks come together to create three course dinners and extend an invitation to the public. Furthermore, Robin Food opens their kitchen and space to anyone with a project aimed at reducing food waste or preaching sustainability (figure 4b). During the Covid-19 pandemic, the collected food that could not be used for dinners, was divided over recycled plastic bag and could be picked up in oud-west, or was brought to the house of people who really need the food by cargo bike (figure 4c).

While BuurtBuik, a collective with multiple locations in outskirts of the city, focusses on inclusivity and bringing together people from the neighbourhood that have low incomes by serving free meals made from food waste, the visitors of Taste Before You Waste (TBYW) are less diverse and mostly have a higher income. The collective is very well-organised with biweekly dinners on Monday and Wednesday in their space that can host up to 200 people. The organization is currently operated by two full-time coordinators that receive an income and an average of 180 volunteers. Food that is donated by the local Turkish and Moroccan shops in the east of Amsterdam gets picked up by cargo bike, gets cleaned, and cut and prepared by volunteers that arrive in the early afternoon. In the proceeding hours, additional volunteers arrive to greet guests and serve the 3-course menu as waiters to the dinner guests. At the end of the evening, a third set of volunteers arrives to finish the dinner off by cleaning the space and preparing it for the next day. During the dinner evening, guests are educated about where the food comes from, the importance of food waste prevention as well as other relevant topics regarding the well-being of our planet. TBYW makes a free supermarket with the excess food waste, a concept that is also executed by the located in western outskirts of the city Kaskantine. De Kaskantine’s aim is to live and operate off the grid with the intention of sharing their knowledge with the community. Around 60-100 people with low incomes in the neighbourhood visit the free supermarkets and nearly 200 people enjoy the brunches each time that were hosted on Sundays. They strive to educate the city about topics like closing resource loops, producing energy, storing and using rainwater, including an open-source website where everyone can get inspired to use their designs and producing and rescuing food on different wastelands that are dedicated to them by the City of Amsterdam. There is a lot of passion needed to keep such projects running, a full-time job, without making an income and the constant chance to be sent away because more profit can be made by building high rise and office buildings in the city, and building the whole project again in a new location.

Those food rescue organisations are extremely dependent on the donation of food waste from mainly the Food Center, that is planning to cut those relationships in exchange for bringing the food waste to an organic treatment facility to be converted into biofuels. Plans are in the making and execution already to collect data about willingness to donate their food waste of every shop in Amsterdam with the plan of placing those on a map. This map is to be made open-source so that every interested individual or collective can go to the shop and ask for their food waste. The collective doing this is called Wasted Playground and also organises Food Waste tours in Amsterdam to teach inexperienced but interested people how to ask for food donations and make this a more accessible method of obtaining food.

SOLIDARITY

Many of the above-mentioned collectives and individuals relate most to the anarchist movement and become more and more anti-government. By visualising their effort against their income, their addition to society against space they receive from policy makers, this could be understood. I would like to conclude this essay with a wish for more solidarity within the City of Amsterdam. I hope that the policy-makers more and more realise how important togetherness and circularity are and that those grass-rooting collectives throughout the city have an immense potential to add to that, but the only thing they need is some space and trust.

RESOURCES

Davis, O., & Geiger, B. B. (2017). Did Food Insecurity rise across Europe after the 2008 Crisis? An analysis across welfare regimes. Social Policy and Society, 16(3), 343-360.

European commission (2019). Date marking and food waste. Retrieved January 8, 2021, via https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/food_waste/eu_actions/date_marking_en

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2011). Global food losses and food waste. Rome,

Italy: United Nations

Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M., & Hultink, E. J. (2017). The Circular Economy–A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of cleaner production, 143, 757-768.

Gemeenteraad Haarlemmermeer (2006). Afvalstoffenverordening gemeente Haarlemmermeer 2006, article 11.2. Retrieved January 18, 2021 via https://decentrale.regelgeving.overheid.nl/cvdr/XHTMLoutput/Actueel/Haarlemmermeer/CVDR14569.html

Gustavsson, J., Cederberg, C., Sonesson, U., Van Otterdijk, R., & Meybeck, A. (2011). Global food losses and food waste. SIK – The Swedish Institute for Food and Biotechnology.

Harvey, D. (2008). The right to the city. The City Reader, 6, 23-40.

Hodges, R. J., Buzby, J. C., & Bennett, B. (2011). Postharvest losses and waste in developed and less developed countries: opportunities to improve resource use. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 149(S1), 37.

Jansen, J. E. (2016). Vuilnis in het vermogensrecht, NJB 258

Koester, U. (2014). Food Loss and Waste as an Economic and Policy Problem. Intereconomics . 49(6), S.348-354.

Lee, P., Osborn, S., & Whitehead, P. (2015). Reducing food waste by extending product life. WRAP

Loorbach, D. (2010). Transition management for sustainable development: a prescriptive, complexity‐based governance framework. Governance, 23(1), 161-183.

LoveFoodHateWaste, 2020. Everything you need to know about expiry dates. Retrieved January 17, 2021 via https://lovefoodhatewaste.co.nz/reduce-your-waste/reduce-your-wasteunderstand-use-by-and-best-before-dates/

MacArthur, E. (2013). Towards the circular economy. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2, 23-44.

Montanari, M., 1999. Der Hunger und der Überfluss (Hunger and opulence). Beck´ sche Reihe 4025, Verlag Beck, Munich (special issue)

Rijksoverheid (2019). Uitvoeringsprogramma Circulaire Economie 2019-2023. Circulaire Economie.

Rocco, R. (2013, June 14). What is governance and what’s it for? [Powerpoint slides]. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.slideshare.net/robrocco/what-is-governance-and-whats-it-for

Rocco, R. (2017, October 31). Spatial Justice and the Right to the City [Powerpoint Slides]. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.slideshare.net/robrocco/spatial-justice-and-the-right-to-the-city

Rocco, R. (n.d.). Why governance will make urban design and planning better: Dealing with the communicative turn in urban planning and design. Retrieved January 7, 2021 via http://www.worldurbancampaign.org/roberto-rocco#_ftn1

Schneider, F. (2013). The evolution of food donation with respect to waste prevention. Waste Management, 33(3), 755-763.

Schubert, E., 2006. Essen und Trinken im Mittelalter (Eating and Drinking in the Middle Ages). Primusverlag, Darmstadt

Searchinger, T., Waite, R., Hanson, C., Ranganathan, J., Dumas, P., Matthews, E., & Klirs, C. (2019). Creating a sustainable food future: A menu of solutions to feed nearly 10 billion people by 2050. Final report. WRI.

Soja, E. (2009). The city and spatial justice. Justice spatiale/Spatial justice, 1(1), 1-5.

Stenmarck, Â. Soja, E. (2009). The city and spatial justice. Justice spatiale/Spatial justice, 1(1), 1-5.Quested, T., Moates, G., Buksti, M., Cseh, B., … & Östergren, K. (2016). Estimates of European food waste levels. IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute.

Tansley, A. G. (1935). The use and abuse of vegetational concepts and terms. Ecology, 16(3), 284-307.

Tonini, D., Wandl, A., Meister, K., Unceta, P. M., Taelman, S. E., Sanjuan-Delmás, D., Dewulf, J., Huygens, D. (2020). Quantitative sustainability assessment of household food waste management in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 160.

Tuominen, L. (2010, March 20). Reductionism And Systems Thinking: Complementary Scientific Lenses. Retrieved December 11, 2020 via http://www.science20.com/knocking_lignocellulosic_biomass/reductionism_and_systems_thinking_complementary_scientific_lenses

United Nations. (2018). Sustainable development goals. United Nations. United Nations Sustainable Development.

Vinegar, R., Parker, P., & McCourt, G. (2016). More than a response to food insecurity: demographics and social networks of urban dumpster divers. Local Environment, 21(2), 241-253.

Wigger, A. (2014). A critical appraisal of what could be an anarchist political economy.